For these three trailblazers, Oxford was not just a University. It was the place where they would begin to make their names.

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wilde Wills (1854-1900) was Ireland’s greatest wit and dandy. He is one of English literature’s most famous authors and a gay icon. Born in Dublin, Wilde took a degree in Classics and won the Berkeley Gold Medal for Greek at Trinity College Dublin. By all accounts he was academically successful but socially unremarkable. His classmates thought him awkward and mopey. All this was to change at Oxford – or so he hoped.

He arrived the day after his twentieth birthday, and as a student at Magdalen College, from 1874-1878, took his first steps towards fame. But he was not the greatest student celebrity in Oxford – he had competition from others like Christian Cole and His Royal Highness Prince Leopold, Queen Victoria’s youngest son. In 1882-1883, Wilde toured the United States lecturing on art and interior decoration. During this time, he was ridiculed in anti-Irish caricatures, portrayed in blackface, and embroiled in racial controversies and sex scandals because of his ambiguous ethnicity and gender identity. In the video below, Prof. Michèle Mendelssohn discusses the anti-Irish sentiment Wilde endured during his American lecture tour:

On his return to England, he married Constance Lloyd and fathered two sons. For the better part of the 1880s and early 1890s, he edited The Woman’s World magazine and penned critical essays, stories and fairy tales. The Picture of Dorian Gray, his 1890 novel, alluded to homosexuality and fell afoul of Victorian morality. With witty comedies like The Importance of Being Earnest, he gained acclaim and transformed the theatre through barbed critiques of English society.

In 1895, at the height of his success, the public scandal over his homosexual love affair with Magdalen alumnus Lord Alfred Douglas led to him being accused of violating section 11 of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which forbade “acts of gross indecency between men.” Wilde’s affairs were outed in London’s Old Bailey, where he faced his accusers and went on record about the dramas of homosexual souls across the ages, declaring:

“The love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo … It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the “love that dare not speak its name,” and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it.

With this speech, Wilde placed himself as one of the last in a line of misunderstood men stretching back millennia. He was convicted and sent to prison with two years’ hard labour. “It is the worst case I have ever tried,” Justice Wills declared, adding that he thought the sentence inadequately severe.

Wilde instantly moved from the hub of English society to solitary confinement. Life as he knew it ended, and the grim life of convict C.3.3. began. Bankrupted and humiliated, his name became synonymous with shame. After his release, in 1897, he was a broken man. He never saw his children again. Condemned to live his final years in exile, he lived anonymously in Europe and died at the age of 46. Homosexuality was decriminalized in England in 1967.

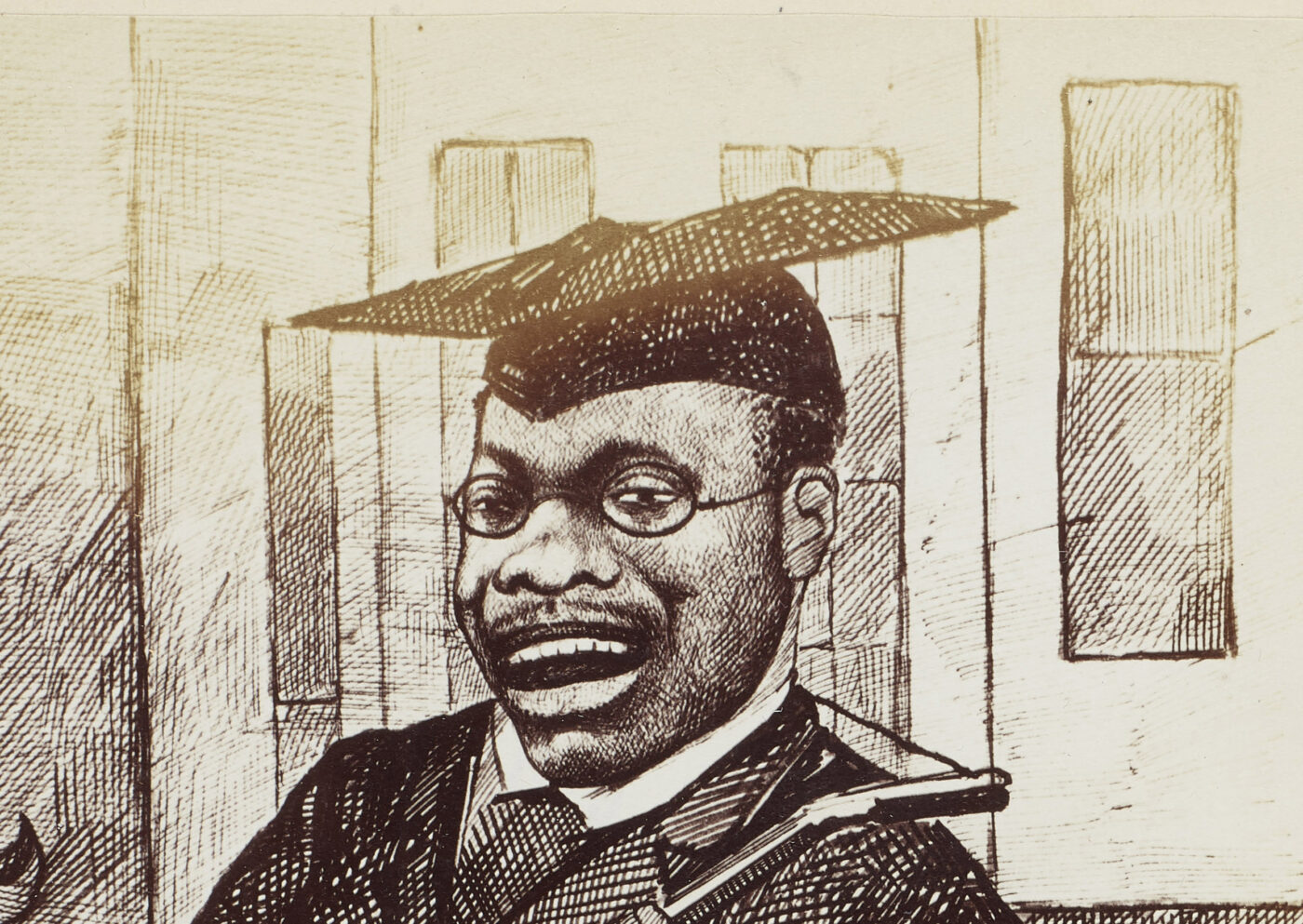

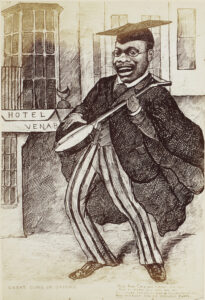

T. Shrimpton, ‘Old King Cole’ from 1224 caricatures of Oxford life.

Reproduced by kind permission of The Bodleian Libraries, The University of Oxford: G.A. Oxon 4o 414, fol. 533.

Christian Frederick Cole (1852-1885) is believed to be the first Black African awarded a University of Oxford degree. He was also the first Black African to practice law in an English court. Born in Waterloo, Sierra Leone, Cole began his studies at Oxford in 1873, a year ahead of Oscar Wilde. Both studied Literae humaniores (also known as “Greats”), a degree combining Greek and Latin, history, and philosophy. Until Cole graduated in 1876, he was a non-collegiate student. He was a member of University College from 1877 to 1880. An energetic anti-imperialist, Cole spoke at the Oxford Union in favour of self-government for India and against British imperial federation and governmental paternalism.

Despite dying of smallpox at the age of 33, Cole certainly had an extraordinary life that spanned continents. He was called to the Inner Temple in 1883 and later worked in East Africa. Dr Philip Burnett, Assistant Librarian at University College, discusses his varied life in the video below.

Cole claimed he was the first Black African student, and this has not been disputed. The University did not keep records of race at this time. It is possible there were others before him, however. Half a century earlier, two Black West Indian students studied at Oxford, Alexander Heslop (B.A. Queen’s College, Oxford 1835) and Peter Moncrieffe. This exhibition showcases recent archival finds that illuminate Cole’s political passions and student celebrity. Still, little is known about the substance of his life. More research is needed to retrieve the University’s Black history.

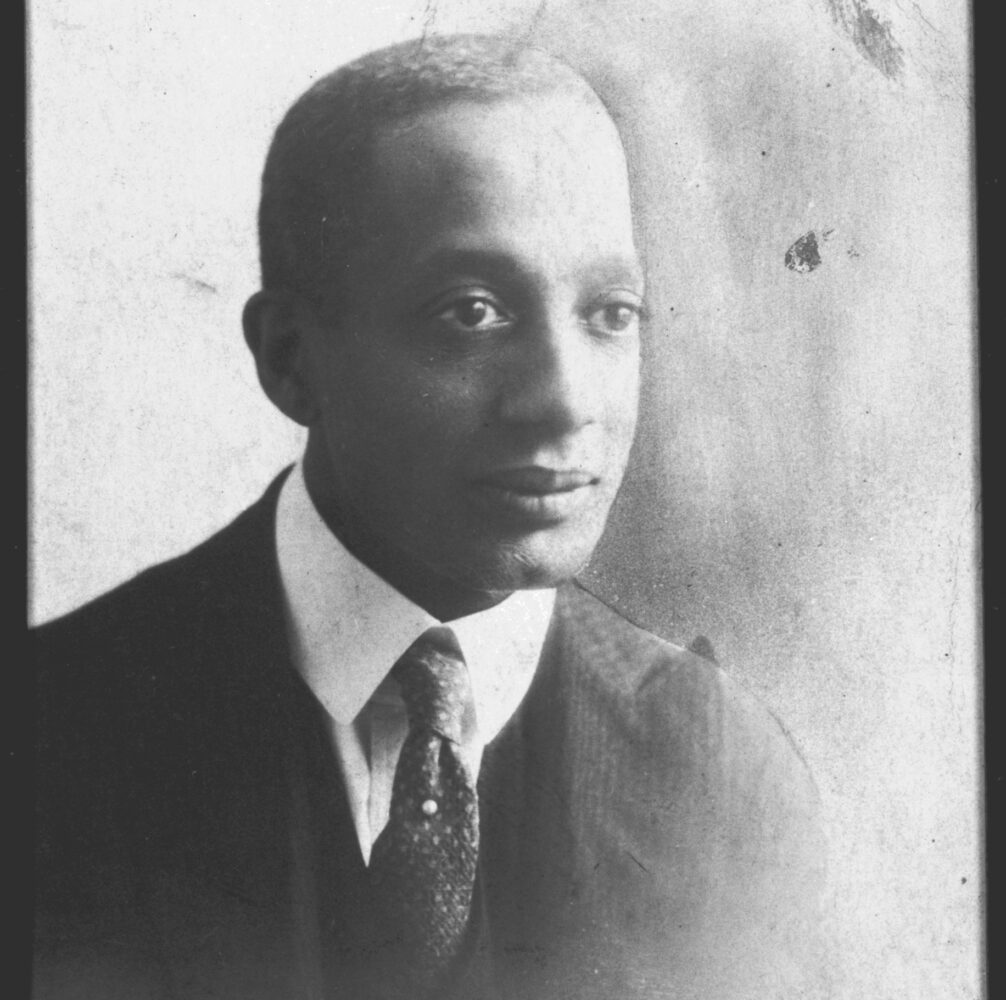

“Alain LeRoy Locke of Pennslyvania, first colored winner of the Cecil Rhodes Oxford Scholarship” from the The A.M.E. Church Review, vol. 24 no. 1, July 1907

Alain LeRoy Locke (1885-1954) was the first African American Rhodes Scholar. Later, he became the dean of the Harlem Renaissance or New Negro movement, which championed 20th century Black arts and culture. Born in Philadelphia, USA, to two teachers, he graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1907, where he studied with eminent philosophers and critics including George Santayana, Josiah Royce and Irving Babbitt. He completed his degree in three years (rather than the usual four) and wrote an essay on Tennyson that won Harvard’s most distinguished essay prize. He joined Hertford College, Oxford in 1907 after five rejections (it was not unusual for Rhodes Scholars to apply to more than one college before being accepted).

As a young gay man, Locke saw art as a way out of conventional morality. He was a devotee of Oscar Wilde, finding the Irishman artistically inspiring and sexually chastening. “It is Oscar Wilde,” he wrote in a Harvard essay, “who seems fated to tell us ‘Don’t let us go to life for our fulfilment, for our experience.’” Like his Oxford hero, Locke initially applied to Magdalen College, wanted to study “Greats” and dressed with panache. Physically, they could not have been more different: standing 6’4” tall, brawny Wilde could easily look like a backwoodsman, while elfin Locke measured 4’11” and weighed 95 pounds.

According to Jeffrey Stewart, Locke’s biographer, his homosexuality enabled him to see through “the hypocrisies of a heterosexual bourgeois society but also that his outsider position left him vulnerable. There were limits to how much he felt he could rebel against such a society without being exposed. Wilde had been targeted as much for his scathing criticisms of bourgeois British society as for his sexual orientation.”

After Oxford, Locke became a professor at Howard University in Washington, DC. During the 1920s and 1930s, he nurtured a generation of outstanding Black artists and advocated for African-Americans. In 1925, he edited The New Negro: An Interpretation. This anthology of fiction, poetry, and essays on African and African-American art and literature became an influential text. Rhodes Scholar Camille Borders, MPhil student at Magdalen, discusses what the exhibition means to her as a historian:

He believed that African-American culture would foster social integration and act as a bulwark against racism. He died aged 68. His magnum opus, The Negro in American Culture, was published posthumously in 1954. He wrote that “the American Negro is sensitive to the plight of oppressed and minority peoples everywhere… cultural pluralism is indigenous to American democratic principles, though it has been placed in doubt in the course of American history. But as we face the compulsions of our time, we must restore this vital concept to our thinking and to our domestic and foreign policy.”